Ensuring a universal access to water

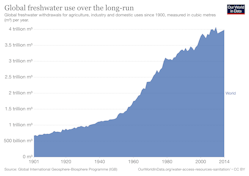

With growing world population, water consumption is doubling every thirty years. Water resources are getting spares and some countries are testing water privatization as a solution, unfortunately often at the expense of their citizens and farmers. For the European Sustainable Developpement week, Katia Nicolet, the science advisor of Energy Observer, highlights the dangers of privatization and the necessity to keep water access as a Human Right for all.

Water as a right, by SDG 6: “Clean water and Sanitation”

Access to safe, sufficient and affordable water is recognized by the United Nations as a human right. Essential for the health, dignity and prosperity of people, access to water is a pre-requisite to the realization of other human rights. Water facilitates most of our human needs: we need it to drink, to maintain minimum hygiene, to clean and cook, to grow food, to sustain livestock, to manufacture products, and to generate electricity. It simply would not be possible for any human being to live a single day without needing water directly or indirectly for survival.

SDGs challenges in developing countries

With growing world population, water consumption is doubling every thirty years (average since 1900), a growth that cannot be sustained much longer. Even some of the water-richest countries in the world, like Brazil, Canada and the US are seeing their lakes shrink, their rivers dry up and some areas are experiencing extreme droughts. The overconsumption of water by the agricultural, manufacturing and energy sectors, in order to sustain our lifestyle, is depleting our freshwater resources. This unsustainable use of water is destructive and is one of the biggest challenges our societies face today.

One of the strategies to regulate water consumption that is being advocated by the financial sector is water privatization. So, what does that mean exactly and what are the potential consequences of such decision?

Water privatization for the benefit of shareholders: the UK

By privatizing water supply and distribution, water stops being a free commodity for all and becomes a lucrative resource. The argument put forward by the supporters of privatisation is that water is precious, and its utilisation needs to be carefully managed to avoid waste. The only way to do so, according to some like Willem Buiter, a special financial advisor at Citigroup Bank, is for everyday consumers to “feel [the cost of water] in their wallet”.

One early European example of water privatization is the United Kingdom. In 1989, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, transferred the provision of water and wastewater services in England and Wales to the private sector. Back then, the national water authorities lacked investment from the central government and were chronically underfunded. This led to infrastructure degradation, river pollution and decline of tap water quality. After the transfer to the private sector, the network received a considerable upgrade and soon was able to comply to the European Union standards and legislations.

Despite its initial benefits, the UK water privatisation came with a cost. As with any private enterprise, the overarching aim is not the benefit of its customers, but the profit of its shareholders. Research from the University of Greenwich evaluated that £1.8 billion are given every year as dividends to shareholders and £500 million per year are spent as interest payments on debt. These combined spending of £2.3 billion per year are payed for by the consumers, which equates to roughly £100 per year per household. If this service was to be nationalised again, each household would see their water bill cut down by about 25%.

Thirty years after the transfer of water provision to the private sector, UK citizens pay an excess of £2.3 billion every year for a service equivalent to that of other EU countries with nationalized water supply, a surplus that goes into the pockets of private shareholders.

A market that benefits larger companies: the Australian example

In 2007, Australian authorities enacted the Water Act, a law to better manage Australia’s water resources in the national interest, and optimise economic, social and environmental outcomes. Simply put, Australian water reserves are evaluated every year and quotas are given to the bigger consumers (farms, industries and cities) according to their needs and the weather forecast. Along with this law, a new Water Market was created where consumers could buy extra water rights or sell some of their rights in case of water excess. Unfortunately, the market also opened to outside investors, individuals and companies that never physically acquired any water, but speculate on its price according to supply and demand.

The problem now is, the price of water does not reflect the real value of water, but the fictional state of the market. Since the market first opened, the price of water increased 14-fold from $50 to almost $700 Australia dollars per 1 million litres. On top of the price hikes, brokerage companies and their investors capitalise on droughts and water scarcity, thus making a profit on climate change. While shareholders profit, farmers are going bankrupt. Family owned businesses and small to medium sized farms cannot afford today’s water prices. In drought years, their quota is reduced to a bare minimum, forcing them to buy more water at a higher price if they want their livestock or crops to survive.

Many farmers have had to sell their farms in the past 10 years due to the creation of the water market. The only beneficiaries are the mega farms, who often own large catchments of water and make profit on its market value. The over pricing of water also selects for larger sized, industrial monocultures, to minimise water usage per unit of production. But ultimately, the loss of diversity in crop production will impact other areas of the economy, such as import and export.

To privatize is not to protect

In the face of climate change, unprecedented weather patterns are becoming the new normal. In Australia, nine of the ten warmest years on record have occurred since 2005 and the warmest of all was the latest, 2019. The annual national mean temperature in 2019 was 1.5˚C above average. These trends are becoming widespread with record droughts and temperatures being observed globally.

Fearing for the future of their country, Australian environmental organizations have entered the water market in order to buy water, take it out of the market and move it back into sanctuaries. The overarching aim being the preservation of lakes and rivers for the conservation of natural ecosystems.

Americans are now following suit, and California has become a pioneer in this liquid market. The state, at present, has one of the most engineered and over-subscribed water systems in the world, meaning that more water is promised to users than is available. The solution put forward is the same as what Australians signed up for 10 years ago, a water market based on groundwater availability. Just like the Australian example, the Californian market is publicly available to all stakeholders: farmers, communities, regulators and environmental organizations. The Nature Conservancy, one of the largest environmental agencies in the world, is pushing for such a market to be opened, seeing it is a useful tool for nature and water conservation.

Environmental organizations in developed countries are now joining these markets, raising money from crowd funds, buying water shares and returning water to the rivers and lakes it originally came from. But where is this money going then? If the United Kingdom and Australia are any example, the ones getting rich are not the costumers in cities or the farmers ploughing the fields, it is the private investors.

Abuse and speculation

In this liberal world where water is a lucrative investment like any other, every day people are giving money to environmental agencies to return water to nature, while paying a higher price on water bill. Farmers and small businesses are struggling to afford the water they need to feed us all while millionaires are accumulating virtual water in their bank account despite having never physically owned any.

As the severity of climate change impacts and droughts worsen every year, the rich will continue to profit and fill their pools while the poor struggle to afford access to the water they desperately need to survive.

Access to water should not be about charity, it is a human right.

To go further :

- Privatization of Rio Water Utility Raises Concerns About Access for Favelas - The Rio Times

- The Middle East is thirsty for solutions to water scarcity - The National

- Water wars: How conflicts over resources are set to rise amid climate change - World Economic Forum